|

| Magellan's starving fleet traveled 1,100 nautical over one week. |

On March 16, 1521, Ferdinand Magellan's fleet reached the Visayan Islands—Spain's debut in the Philippines—where they finally found a safe place to land and get food after three deadly months at sea.

The fleet chanced upon Guam a week earlier, but wound up fighting with the Chamorro there. Seven Chamorro were killed and some forty houses burned. Soon after, Magellan's struggling three-ship armada, in beat-up condition, was chased off by more than a hundred of the Chamorro outrigger canoes—for quite a distance.

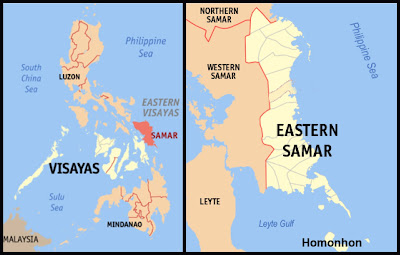

The fleet first spotted the peaks of Samar, a large island on the eastern edge of the Visayas, where coastal reefs made an attempt at landing too dangerous. Magellan continued to the south, then west into the Leyte Gulf, where the crew sighted canoes—maybe a good sign, but possibly a bad one, considering their welcome at Guam.

At dawn on Saturday, March 16, 1521, we came upon a high land at a distance of three hundred leguas from the islands of Latroni—an island named Zamal [i.e., Samar]. The following day, the captain-general desired to land on another island which was uninhabited and lay to the right of the abovementioned island, in order to be more secure, and to get water and have some rest. He had two tents set up on the shore for the sick and had a sow killed for them.

On Monday afternoon, March 18, we saw a boat coming toward us with nine men in it. Therefore, the captain-general ordered that no one should move or say a word without his permission. When those men reached the shore, their chief went immediately to the captain-general, giving signs of joy because of our arrival.

Five of the most ornately adorned of them remained with us, while the rest went to get some others who were fishing, and so they all came. The captain-general seeing that they were reasonable men, ordered food to be set before them, and gave them red caps, mirrors, combs, bells, ivory, bocasine, and other things. When they saw the captain’s courtesy, they presented fish, a jar of palm wine, which they call uraca [i.e., arrack], figs more than one palmo long [i.e., bananas], and others which were smaller and more delicate, and two cocoanuts. They had nothing else then, but made us signs with their hands that they would bring umay or rice, and cocoanuts and many other articles of food within four days.

By John Sailors

Enrique's Voyage

(C) 2023 by John Sailors. All rights reserved.

Magellan Reaches Guam: Chamorro Outriggers Take On Spanish Carracks

Antonio Pigafetta's account of the Magellan-Elcano voyage gives us both first-hand historical detail and color—the human aspects of the journey. The Italian scholar learned all he could about the cultures that Magellan's fleet encountered, even sitting down and recording samples of languages.

An excellent example of Pigafetta's curiosity and fascination is his description of the coconut and the palm tree, which he learned about soon after the fleet's arrival in the Philippines. Like the pineapple Magellan tried in Rio, the coconut was an unknown. "Cocoanuts are the fruit of the palmtree. Just as we have bread, wine, oil, and milk, so those people get everything from that tree. Read more.

A handful of medieval travelogues were the closest thing Ferdinand Magellan had to a travel guide when he sought a westward route to Asia—accounts credited to Marco Polo, John Mandeville, and others, and those all echoed the same monsters and myths repeated since the time of Pliny the Elder, the Roman author whose Naturalis Historiae helped inspire the encyclopedia.

It gets little mention today, but The Travels of Sir John Mandeville was a world atlas of sorts in medieval Europe, essential reading for navigators and explorers. The accounts became circulated widely in Europe in the fourteenth century. They detail travels in North Africa and the Middle East, and in India, China, and even the Malay Peninsula—which would have been of particular interest to Ferdinand Magellan, and also Enrique of Malacca, Magellan’s interpreter-slave. Read more.

- EnriqueOfMalacca.com

- Enrique of Malacca on Twitter

- Enrique of Malacca on Facebook

- John Sailors / Enrique on Medium

- And, yes, Enrique might be 500 years old, but he was known as a kid, so of course he's now on Instagram too.