|

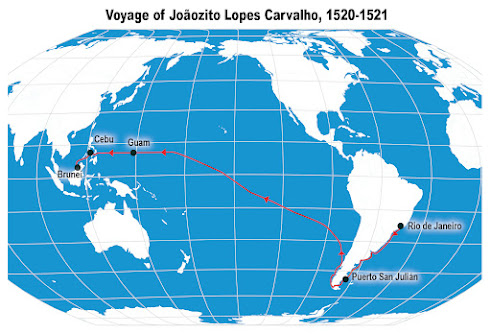

| Born at Guanabara Bay (Rio), Joãozito Lopes Carvalho was seven years old when he joined Magellan's fleet. |

Ferdinand Magellan’s historic journey swept up several unlikely travelers along the way, among them a seven-year-old boy at Guanabara Bay (Rio de Janeiro). Half-Portuguese, half-Tupi Indian, he is remembered in history as Joãozito Lopes Carvalho. The young boy became the first native of Brazil and likely all of South America to cross the Pacific Ocean—on a year-and-a-half journey that for him ended at Brunei five hundred years ago this summer.

|

| Cabral's first landing in Brazil, 1502. |

Joãozito was the son of João de Lopes Carvalho and a Tupi Indian woman in what is now Brazil. A Portuguese pilot, João Carvalho had traveled to Guanabara Bay in 1512 on the Bertoa, a commercial vessel sent to pick up dyewood there. A decade earlier a Portuguese fleet had landed at Guanabara Bay and claimed the area for Portugal, naming it Rio de Janeiro for the month they arrived, January 1502.

After his 1512 journey, Carvalho stayed behind for four years, possibly to manage a storage facility. During that time, he took a native mistress and apparently fathered the child.

Carvalho returned to Portugal in 1517, where his experience along the Brazilian coast caught Magellan’s attention. He accompanied Magellan from Lisbon to Spain and was Magellan’s original choice for captain of the ship Santiago, although Spanish trade officials objected because Carvalho was Portuguese.

Instead, Carvalho was made pilot of the Concepción, a 90-ton vessel whose 45-man crew included Captain Gaspar de Quesada and Master Juan Sebastián Elcano. Quesada became a leader of the failed Easter mutiny in April 1520 and was executed—and quartered—shortly after. Elcano survived the mutiny to later become captain of the Victoria. As such Elcano led the completion of the famed circumnavigation, bringing Victoria back to Seville.

As Magellan’s fleet neared the South American coast, Carvalho assured the Captain General that Guanabara Bay was a safe place to stop for provisions. Magellan worried about a run-in with Portuguese there, but Carvalho assured him that the friendly natives would provide the fleet with fruits, vegetables, fish, and game.

Carvalho may also have been eager to visit the friendly women of Guanabara, whose promiscuousness would create problems for Magellan. One can imagine Carvalho exciting lonely sailors on deck with tales of the tropical paradise where “they go naked, both men and women,” as Magellan’s chronicler, Antonio Pigafetta, wrote.

Shortly after the fleet arrived at Rio de Janeiro, Carvalho's mistress appeared and presented the seven-year-old boy. Carvalho acknowledged the child as his and took Joãozito aboard the Concepción as a cabin boy.

It’s hard to imagine what a seven-year-old was expected to contribute on such a journey, and certainly sixteenth century Europeans did not share modern views on child welfare. In fact it was a practice for ships of the day to bring along several child pages, some as young as eight. Many were orphans, some were taken from the streets and forced on board.

The roster for Magellan’s fleet lists two to three cabin boys per vessel, with one on the Victoria. Their duties included tasks disliked by crew such as scrubbing decks and serving meals.

Joãozito may have been spared some of these, since his father was the Concepción’s pilot, a top officer. The ship carried two other cabin boys, a Castilian named Pedro de Chindarza and a boy named Sean (Juan) Irés, listed as from Ireland.(1)

|

| Replica of Victoria, slightly smaller than Concepción. |

Aboard ship the human stench would have been worse. At sea, bathing was difficult, and when crew did bathe, it meant washing with saltwater that irritated skin and left them scratching.

The Concepción carried a crew of 45 men packed into the vessel’s small confines, shared with cargo, provisions, livestock, and at one point (“crammed with”) strange-looking, flightless black “geese” found on an island—the first penguins most of the crew had ever seen (“… they were so fat that we didn’t pluck them but skinned them …”).

Then there were nonhuman smells: the stench of bilgewater rising from the hull, livestock, the slaughtering of livestock, and, as Pigafetta recorded, a note of rat urine.

And penguins.

Equally troubling would have been the food. Joãozito had grown up in a land abundant in fruit, fish, and wildlife. By contrast, the Spanish and Portuguese on land had a diet of meats loaded with spices to cover up the rotting taste, and coarse breads to chase it down. At sea, as soon as fresh provisions ran out—like penguin—fare would have been dried fish, sea biscuit, and whatever various crew cooked up from time to time.

What’s more, for young Joãozito there was no one to complain to about such horrors, and no language to complain in. As quickly as many children pick up second languages, it’s unlikely Joãozito learned much Portuguese from his father in the few weeks at Rio de Janeiro, and aboard the Concepción, the common language was Spanish.

The majority of the crew were Castilian, along with a couple of gunners from Flanders, two Irish, a Genoan, and a sailor from Greece. Carvalho Sr. was one of seven Portuguese in the crew.

Thus during the first weeks at sea, Joãozito’s main means of communication would have been facial expressions and gestures. Grimacing at the constant stench and shoddy fare would have been an early language lesson.

Beyond that for Joãozito Lopes Carvalho, learning survival Spanish literally meant survival.

Notes

(1) Of the other cabin boys on the Concepción, Sean (Juan) Irés, listed on the roster as from Ireland, was one of two Irish crew. The other, William Irés, an apprentice seaman, might have been a brother. William Irés drowned at La Plata (near modern-day Buenos Aires) on Jan. 25, 1520. Sean Irés wound up on the Trinidad after the Concepción was scuttled. He died in October 1522.

The other cabin boy on the Concepción was a Castilian named Pedro de Chindarza, who eventually made it back to Spain, in 1523, after being held for a time in the Cape Verde Islands. He was the fleet’s only cabin boy (of twelve) to return and complete a circumnavigation.

By John Sailors

Coming soon: Check back for Part 2 and Part 3 in this series exploring the journey of Joãozito Lopes Carvalho.

_______________

Journey of Joãozito Lopes Carvalho

• Part I, First South American Native to Cross the Pacific

• Part II, San Julian, the Strait, and the Pacific

• Part III, Cebu, Mactan, and Pirating in Brunei

_______________

(C) 2021 by John Sailors. All rights reserved.

Ferdinand Magellan’s historic journey swept up several unlikely travelers along the way, among them a seven-year-old boy at Guanabara Bay (Rio de Janeiro). Half-Portuguese, half-Tupi Indian, he is remembered in history as Joãozito Lopes Carvalho. The young boy became the first native of Brazil and likely all of South America to cross the Pacific Ocean—on a year-and-a-half journey that for him ended at Brunei five hundred years ago this summer.

Antonio Pigafetta's account of the Magellan-Elcano voyage gives us both first-hand historical detail and color—the human aspects of the journey. The Italian scholar learned all he could about the cultures that Magellan's fleet encountered, even sitting down and recording samples of languages.

An excellent example of Pigafetta's curiosity and fascination is his description of the coconut and the palm tree, which he learned about soon after the fleet's arrival in the Philippines. Like the pineapple Magellan tried in Rio, the coconut was an unknown. "Cocoanuts are the fruit of the palmtree. Just as we have bread, wine, oil, and milk, so those people get everything from that tree. Read more.

A handful of medieval travelogues were the closest thing Ferdinand Magellan had to a travel guide when he sought a westward route to Asia—accounts credited to Marco Polo, John Mandeville, and others, and those all echoed the same monsters and myths repeated since the time of Pliny the Elder, the Roman author whose Naturalis Historiae helped inspire the encyclopedia.

It gets little mention today, but The Travels of Sir John Mandeville was a world atlas of sorts in medieval Europe, essential reading for navigators and explorers. The accounts became circulated widely in Europe in the fourteenth century. They detail travels in North Africa and the Middle East, and in India, China, and even the Malay Peninsula—which would have been of particular interest to Ferdinand Magellan, and also Enrique of Malacca, Magellan’s interpreter-slave. Read more.

Reni Roxas and Marc Singer brought the story of Enrique to life for children in First Around the Globe: The Story of Enrique. Twenty years on they released this anniversary edition in 2017 from Tahanan Books, Manila. Read more.

On March 16, 1521, Magellan and his crew reached the Philippines, where they would finally be able to recover after three months crossing the Pacific. They were unable to stop long at Guam—their encounter with the Chamorros they met there did not go well, as seen in their sendoff. As they were departing, more than a hundred of the Chamorros’ outrigger canoes followed for more than a league.

- EnriqueOfMalacca.com

- Enrique of Malacca on Twitter

- Enrique of Malacca on Facebook

- John Sailors / Enrique on Medium

- And, yes, Enrique might be 500 years old, but he was known as a kid, so of course he's now on Instagram too.