|

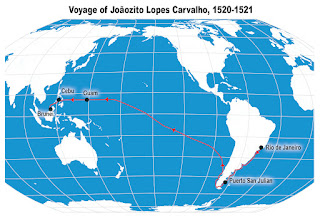

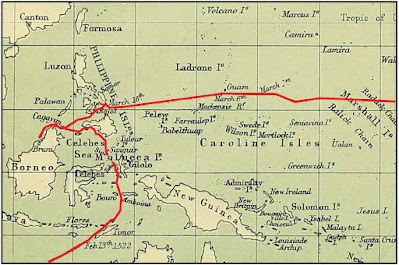

| Armada route through East Asia. |

Joãozito Lopes Carvalho made a historic journey across the Pacific—first native of Brazil. It began at Guanabara when his father, a Portuguese pilot with Ferdinand Magellan’s armada, made him a cabin boy; it ended a year and a half later when Carvalho Sr. left the boy in Brunei, a hostage of the sultan.

After joining Magellan’s fleet at about age seven, Joãozito saw the crew shift collectively from one emotional state to another—terror in initial storms, fury leading up the Easter mutiny, wonder traversing the strait, and starvation and utter despair crossing the Pacific.

That left Joãozito’s father as one of the only senior officers, and according to one account, Carvalho abandoned a weeping Serrano on the beach and set sail. Others have suggested Serrano ordered Carvalho to depart.

In any case, with Magellan, Barbosa, and Serrano gone, Carvalho was elected captain-general (and captain of the Trinidad), even though he was outranked by the Concepción’s master, Juan Sebastían Elcano. It was a choice that proved regrettable for the fleet and disastrous for Joãozito.

With too few men left to sail all three ships, they scuttled the Concepción, the ship in the worst shape, burning it so as to leave no monument behind. Carvalho began as pilot of the Concepción. Joãozito presumably transferred from that ship to the Trinidad with his father.

At this point, the two remaining ships turned into a pirate fleet for a time, capturing and plundering local craft as they went. They wandered for several days to find provisions before kidnapping two Muslim pilots, whom they forced to guide the fleet to Brunei. These were the same tactics that Vasco da Gama and, shortly after, Pedro Álvares Cabral adopted during the first Portuguese forays into India: capturing ships, holding hostages, and forcing local pilots to guide them.

|

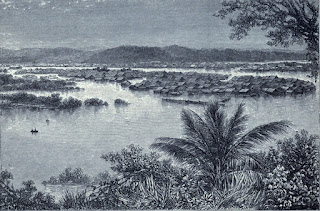

| City of Brunei. |

Antonio Pigafetta, chronicler of the fleet, gave a detailed description of Brunei:

That city is entirely built in saltwater, except the houses of the king and certain chiefs. It contains twenty-five thousand fires [i.e., families]. The houses are all constructed of wood and built up from the ground on tall pillars. When the tide is high the women go in boats through the settlement selling the articles necessary to maintain life. There is a large brick wall in front of the king’s house with towers like a fort, in which were mounted fifty-six bronze pieces, and six of iron. During the two days of our stay there, many pieces were discharged. That king is a Moro and his name is Raia Siripada. He was forty years old and corpulent. No one serves him except women who are the daughters of chiefs. He never goes outside of his palace, unless when he goes hunting, and no one is allowed to talk with him except through the speaking tube.

As at Cebu, word of Portuguese attacks in India and Malacca had preceded them. Possibly with a hint of irony, the armada assured the sultan that they were Spanish, not Portuguese, though the fleet’s commander, Joãozito’s father, was Portuguese, as was Magellan before him. And both Carvalho Sr. and Magellan had previously served the Portuguese king—Magellan at the sack of Malacca.

The fleet was allowed to stay at Brunei and trade for a few weeks, but tensions were constant. The Portuguese historian Gaspar Corrêa told the story in his Lendas da Índia (Legends of India, early 1500s):

Carvalhinho became suspicious … and ordered good watch to be kept day and night, and did not allow more than one or two men to go ashore. The king [sultan] perceiving this sent to beg Carvalhinho to send him his son who had brought the present, because his little children who had seen him, were crying to see him. He sent him, very well dressed, with four men, who, on arriving where the king was, were ordered by him to be arrested.

On July 29, the Spanish ships were approached by a fleet of two hundred pirogues and a battle ensued. The Spanish cannon quickly broke up the attack and moved to safety. The following day they captured a grounded junk and took sixteen hostages, among them a prince from Luzon and three women.

|

| The Victoria. |

As for Joãozito, Pigafetta wrote:

We sent a message to the king [sultan], asking him to please allow two of our men who were in the city for purposes of trade and the son of João Carvalho, who had been born in the country of Verzin [Brazil], to come to us, but the king refused. That was the consequences of João Carvalho letting the above captain [prince] go. We kept sixteen of the chiefest men [of the captured junks] to take them to Spagnia, and three women in the queen’s name, but João Carvalho usurped the latter for himself.

The fleet waited several days for the return of Joãozito and the others but finally departed. Here, Joãozito Carvalho, first native of Brazil to cross the Pacific, disappears from history at the age of eight or nine.

Whatever his fate, he faced inconceivable challenges.

In the year and a half Joãozito spent journeying from Rio to Brunei, he would have become at least functionally bilingual and possibly trilingual. Kids pick up languages fast, and at seven he was stripped from his village and brought to sea. Spanish was the main language of the fleet, and Carvalho Sr. was Portuguese, one of seven in the crew. And given the boredom of life at sea, Joãozito might have wondered also at the speech of the Concepción’s two gunners from Flanders or the two young crewmates from Ireland.

Now Joãozito found himself in the Sultanate of Brunei, in a multilingual port city where not one of his own languages held any currency. When Joãozito joined Magellan’s fleet, daily survival had depended on learning Spanish, just to find food and basic necessities. He had survived that test, but in Brunei Joãozito was starting all over.

By John Sailors

_______________

Journey of Joãozito Lopes Carvalho

• Part I, First South American Native to Cross the Pacific

• Part II, San Julian, the Strait, and the Pacific

• Part III, Cebu, Mactan, and Pirating in Brunei

_______________

Images:

Magellan in Strait: From Giulemard, F. H. H., The Life of Ferdinand Magellan, published by George Philip & Son, Liverpool, 1891, p. 210.

City of Brunei: From Giulemard, F. H. H., The Life of Ferdinand Magellan, published by George Philip & Son, Liverpool, 1891, p. 270.

Victoria: Abraham Ortelius, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

(C) 2021 by John Sailors. All rights reserved.