|

| Duarte Barbosa, Magellan's ally. |

A relation of Ferdinand Magellan’s by marriage, Duarte Barbosa was a key ally on the voyage, yet also a source of trouble more than once.[1] He may also have been among the experienced travelers in the crew, possibly meeting Magellan in India around 1512.

Barbosa in India

|

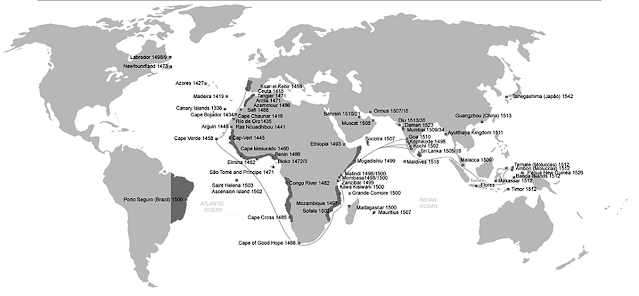

| Portuguese trade routes around Africa and India. Note on the outward route, fleets sailed well into the Atlantic, nearing Brazil, to catch the trade winds. |

Duarte Barbosa was born in Lisbon sometime around 1480. According to Dames, he sailed with the second or third Portuguese fleet to India. The accounts in the book suggest he would have traveled with the second, commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral, the expedition that accidentally “discovered” the Brazilian coast. If so, Barbosa’s stopover in Brazil with Magellan was a return visit.

Dames reported that Barbosa’s father and uncle sailed with those early Portuguese fleets, and Duarte stayed behind with his uncle in Cochin (Kochi) and later transferred to Cannanore (Kannur), where he worked in the Portuguese factory (trading post) in that city. A decade later, Portugal’s viceroy Afonso de Albuquerque used a Duarte Barbosa as an interpreter in a 1514 meeting with Cochin’s raja, where Albuquerque tried to persuade the raja to convert to Christianity.

Dames said Barbosa was among a group of colonists opposed to Albuquerque’s plans for India, which sought to occupy and use Goa as Portugal’s main India outpost — at the expense of already-established bases (and relationships) at Cochin and Cannanore. Barbosa’s opposition to Albuquerque may have led to his being passed over for a top writer’s position at Cannanore. Whatever the cause, Barbosa soon returned to Portugal and then, following his father, went to Seville in 1518, as Dames traced events.

Duarte Barbosa's Colonial Travel Guide

Whoever its author, The Book of Duarte Barbosa provides valuable insight into the Portuguese mindset as their armadas brutally forged a maritime empire around the Indian Ocean and Asia that spanned farther than any before it.

Barbosa's book reads like a colonial travel guide, introducing cities and kingdoms and the various goods they traded in. The writer starts up the East Coast of Africa and moves on to India and beyond. His accounts show an enthusiastic interest in peoples and cultures in India, but the overwhelming impression is its callous outlook on Portuguese excesses.

The Portuguese sailed with orders to “discover” places in Africa and India and where possible wage war on and kill “Moors” (Muslims). Beginning with Vasco da Gama’s first tour up the African coast, the Portuguese responded to all resistance with cannon fire and far worse — details Barbosa took very much in stride.

Stanley, who translated versions of both Barbosa’s and Pigafetta’s manuscripts, commented on this outlook in his introduction to Barbosa’s book.[4]

The piracies of the Portuguese are told without any reticence, apparently without consciousness of their criminality, for no attempt is made to justify them, and the pretext that such and such an independent state or city did not choose to submit itself on being summoned to do so by the Portuguese, seems to have been thought all sufficient for laying waste and destroying it. This narrative shows that most of the towns on the coasts of Africa, Arabia, and Persia were in a much more flourishing condition at that time than they have been since the Portuguese ravaged some of them, and interfered with the trade of all.

Barbosa does just this: He roams from praising the wealth and beauty of cities to offering cold account of their destruction.

Barbosa's Kilwa

Sofala, Kilwa, and Malindi, the

stage of Portugal's colonial forays.

Of Kilwa on the east coast of Africa, Barbosa wrote:

stage of Portugal's colonial forays.

… a town of the Moors, built of handsome houses of stone and lime, and very lofty, with their windows like those of the Christians; in the same way it has streets, and these houses have got their terraces, and the wood worked in with the masonry, with plenty of gardens, in which there are many fruit trees and much water. … the Moors of Sofala, and Zuama, and Anguox, and Mozambique, were all under obedience to the King of Quiloa [Kilwa], who was a great king amongst them. And there is much gold in this town, because all the ships which go to Sofala touch at this island, both in going and coming back.

But …

This King, for his great pride, and for not being willing to obey the King of Portugal, had this town taken from him by force, and in it they killed and captured many people, and the King fled from the island, in which the King of Portugal ordered a fortress to be built, and thus he holds under his command and government those who continued to dwell there.

Barbosa's Mombasa

Farther up Africa's East Coast:

It is a town of great trade in goods, and has a good port, where there are always many ships, … This Monbaza is a country well supplied with plenty of provisions, very fine sheep, which have round tails, and many cows, chickens, and very large goats, much rice and millet, and plenty of oranges, sweet and bitter, and lemons, cedrats, pomegranates, Indian figs, and all sorts of vegetables, and very good water.

But …

This King, for his pride and unwillingness to obey the King of Portugal, lost his city, and the Portuguese took it from him by force, and the King fled, and they killed and made captives many of his people, and the country was ravaged, and much plunder was carried off from it of gold and silver, copper, ivory, rich stuffs of gold and silk, and much other valuable merchandize.

Barbosa's Malindi

… this town has fine houses of stone and whitewash, of several stories, with their windows and terraces, and good streets. … The trade is great which they carry on in cloth, gold, ivory, copper, quicksilver, and much other merchandise, with both Moors and Gentiles of the kingdom of Cambay …

And …

This King and people have always been very friendly and obedient to the King of Portugal, and the Portuguese have always met with much friendship and good reception amongst them.

This was the harsh colonial world where Barbosa and Magellan spent their early careers prior to the Armada de Molucca. This was the mindset they carried when they journeyed through the strait and across the Pacific to the Visayans Islands—to Limasawa, then to Cebu, then to Mactan.

The Magellan Expedition

It’s not certain when Barbosa came to know Magellan. The two may have met in India, possibly in Cochin in 1512–13 during Magellan’s return voyage to Lisbon. By 1518 they were together in Seville, where Barbosa’s father, Diogo Barbosa, had settled and become a distinguished Portuguese expatriate. Magellan married Diogo’s daughter Beatriz Barbosa Caldera in 1517, shortly after arriving in the city.

Along the voyage Barbosa had a mixed record with Magellan. In Brazil, Barbosa joined crewmates in what became an ongoing orgy with local women. Barbosa went AWOL for three days and nights, forcing Magellan to send a squad of marines to arrest Barbosa and clap him in irons. Barbosa got into similar trouble a second time on Cebu, disappearing with local women there.

Magellan Mutiny at Puerto San Julián

Barbosa redeemed himself during the mutiny at Puerto San Julián, where Magellan faced a conspiracy among Castilian captains and officers. Among those who remained loyal was Juan Rodríguez Serrano, captain of the Santiago and possibly a friend of Barbosa’s from his time in India.

With the Santiago next to Magellan’s flagship Trinidad, two carracks were pitted against three that included the powerful San Antonio, the largest of the fleet. Magellan turned the tables with a raid on the Victoria, sending Barbosa to lead a boarding party.

|

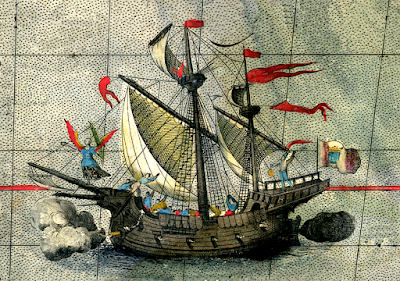

| World map Illustration of the Nao Victoria, the first ship to circumnavigate the globe. |

Magellan rewarded his brother-in-law by making him the Victoria’s new captain. Barbosa commanded the ship that first circled the globe for that key year in the expedition as it passed through the strait and struggled its way across the Pacific.

More ups and downs followed as the fleet reached East Asia. Magellan demoted Barbosa as captain at Cebu after his second AWOL incident, and then, weeks later, the crew elected Barbosa and Serrano to replace Magellan as co-commanders, after their Captain-General’s death at Mactan.

Duarte Barbosa and Enrique of Malacca

It's unknown who devised the plot, but in his journal, Pigafetta blamed the ambush on Enrique of Malacca, Magellan’s slave-interpreter who like Pigafetta was wounded at Mactan. Pigafetta reported:

As our interpreter, Henrich by name, was wounded slightly, he would not go ashore any more to attend to our necessary affairs, but always kept his bed. On that account, Duarte Barboza, the commander of the flagship, cried out to him and told him, that although his master, the captain, was dead, he was not therefore free; on the contrary he [i.e., Barboza] would see to it that when we should reach Espagnia, he should still be the slave of Doña Beatrice, the wife of the captain-general. And threatening the slave that if he did [not] go ashore, he would be flogged …

Magellan stipulated in his will in 1519 that after his death, Enrique was to be freed. According to Pigafetta, Enrique responded to Barbosa’s outburst by going ashore and plotting the attack.

… the latter arose, and, feigning to take no heed to those words, went ashore to tell the Christian king [Humabon] that we were about to leave very soon, but that if he would follow his advice, he could gain the ships and all our merchandise. Accordingly they arranged a plot, and the slave returned to the ship, where he showed that he was more cunning than before.

In retrospect, this can be seen only as conjecture, since no investigation could be carried out. More likely Humanbon, disillusioned and in need or protecting his own future, put the plan in action, possibly getting complicity from Enrique.

The Massacre at Cebu

On May 1, Enrique relayed an invitation from Humabon for the fleet’s captains and officers to attend a banquet, where he would give them jewels to carry back to the Christian king. Twenty-six men went ashore, among them Barbosa, Serrano, and other top officers.

At the last minute, two of them, João de Lopes Carvalho and Gonzalo Gómez de Espinosa, grew suspicious and hurried back to the ships. Just as they arrived, the crew heard shouting from beyond the beach. According to Pigafetta, who was wounded and stayed on board:

Twenty-four men went ashore, among whom was our astrologer, San Martín de Sivilla. I could not go because I was all swollen up by a wound from a poisoned arrow which I had received in my face. Jovan Carvaio and the constable returned, and told us that they saw the man who had been cured by a miracle take the priest to his house. Consequently, they had left that place, because they suspected some evil. Scarcely had they spoken those words when we heard loud cries and lamentations.

We immediately weighed anchor and discharging many mortars into the houses, drew in nearer to the shore. While thus discharging [our pieces] we saw Juan Serrano in his shirt bound and wounded, crying to us not to fire any more, for the natives would kill him. We asked him whether all the others and the interpreter were dead. He said that they were all dead except the interpreter.

He begged us earnestly to redeem him with some of the merchandise; but Johan Carvaio, his boon companion, [and others] would not allow the boat to go ashore so that they might remain masters of the ships. But although Juan Serrano weeping asked us not to set sail so quickly, for they would kill him, and said that he prayed God to ask his soul of Johan Carvaio, his comrade, in the day of judgment, we immediately departed. I do not know whether he is dead or alive.

The three ships left immediately, so details of the attack were never learned. Enrique of Malacca was never again seen by the Europeans.

Again, if Magellan's Barbosa was the travel chronicler, his death at Cebu possibly meant a huge loss of historical knowledge. And had Pigafetta not been injured at Mactan, he too would have attended the banquet and been killed, and we would know very little about the expedition today.

As for Juan Serrano, he was last seen beaten on the beach. He may have been killed there, though it’s been suggested he was kept alive and sold as a slave, possibly in China.

Notes:

1. It is known through records that Duarte Barbosa was a relation of Ferdinand Magellan’s through marriage, possibly Magellan’s brother-in-law or his wife’s cousin.2. This is a good point to stop and remember that history is written not by the victors but by the victors’ writers. Had Barbosa survived to write his own account of the expedition, we might have a very different picture of events and of the people involved. (Treat and pay your writers well.)

By John Sailors

Images:

• Barbosa. Public domain.

• Portuguese trade routes. Walrasiad, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

• Portuguese trade empire. Creative Commons license. Wikimedia Commons.

(C) 2022, by John Sailors.

The Book of Duarte Barbosa Online

Below are English translations of two Barbosa manuscripts, one an original, the other in Italian. The translators/editors of both provided introductions with valuable history on Barbosa and the manuscripts. For an introduction to the manuscripts, check the Resources page at EnriqueOfMalacca.com.

A DESCRIPTION OF THE COASTS OF EAST AFRICA AND MALABAR IN THE BEGINNING OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY (Ramusio translation)

BY DUARTE BARBOSA, A PORTUGUESE

TRANSLATED BY THE HON. HENRY E. J. STANLEY.

Introduction by Henry Edward John Stanley, translator and editor.

From Gutenberg.com.

The Book Of Duarte Barbosa Vol. 1

by Dames, Mansel Longworth, Tr.

From Internet Archive / Archive.org.

The Book Of Duarte Barbosa Vol. 2

by Dames, Mansel Longworth, Tr.

From Internet Archive / Archive.org.

Maps

• Ptolemy World Map

• Fra Mauro Map

• Cantino Planisphere

• Contarini-Rosselli Map

• Johannes Ruysch World Map

.

Frequently Asked Questions

Eat at Joe's.