|

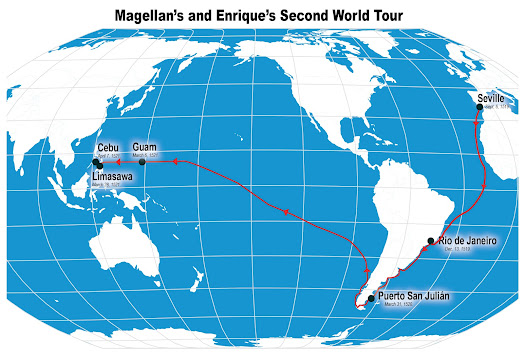

| Route of the Magellan-Elcano expedition, first half. |

(Profiles: Magellan, Part 3.)

Just to get launched Ferdinand Magellan fought dangerous resistance from his own backers—intrigue and sabotage by Castilian officials and conspiracies among top officers in the fleet to mutiny once underway. Portugal was also trying to stop him, by assassination or sinking if necessary.

Crossing the Atlantic, exploring the South American coast beyond the end of the map, and finding his strait—these were only a few of the challenges Magellan faced in his quest to reach the Spice Islands.

On September 20, 1519, Magellan’s Armada de Molucca departed Sanlúcar de Barrameda, south of Seville, with five ships and around 270 men, two-thirds of them Spanish, the rest Portuguese (31), Italian (29), and French (17), as well as Flemings, Greeks, Irish, English, and others.

King Charles named Magellan captain-general of the fleet, but from the start he had to enforce his authority with an iron hand. In Asia a decade earlier Magellan had been more soldier than sailor (though his early education at the court in Lisbon had opened up the world of navigation to him).

Magellan’s authority was challenged before the fleet crossed the Atlantic, but the battle-hardened soldier held firm, arresting the San Antonio’s captain, Juan de Cartagena, for insubordination.

Later, at Puerto San Julian, Magellan faced an outright mutiny by three of the fleet’s five ships. Again, Magellan prevailed, this time with a battle at sea that included sending Duarte Barbosa to board one of the ships and retake it by force.

After a court-martial, Magellan ordered the beheading and quartering of two of the mutineers (one of them already killed in the fight) and had their body parts displayed on poles. Two others were stranded on a nearby island.

|

| Balboa discovers Pacific. |

Magellan remained undeterred; he was determined to reach the Moluccas and join his friend Francisco Serrão. Figuring the islands would be only weeks beyond the end of the strait, Magellan proceeded without stopping to replenish supplies. It was the sort of stubbornness that had gotten other fleet commanders into trouble, including Vasco da Gama, who tried crossing the Indian Ocean with the monsoon against him.

Instead of weeks, Magellan’s fleet spent three months crossing the ocean that Magellan called Mar Pacifico, or “Peaceful Sea.” More than twenty crew died from starvation and scurvy before they finally reached land in Asia.

|

| Reception of the Manila by the Chamorro at Guam, c. 1590. |

On March 6, 1521, the fleet finally reached land, an island where stopping was possible. Magellan had chanced upon Guam and was about to have Europeans’ first encounter with the Chamorro people. Wrote Antonio Pigafetta, the fleet’s chronicler:

Magellan had again failed to learn from mistakes made by Portuguese commanders in Asia. He did not understand the customs of the Chamorro people, who were cut off from the world and had a different understanding of ownership. (When Vasco da Gama reached India, he though the Hindus he met there were eastern Christians, and he didn’t understand why the rulers (of these wealthy trade centers) were unimpressed by his bells and mirrors, as peoples in the Americas proved to be.

|

| Limasawa, Philippines. |

Desperate and with men still dying, Magellan led the fleet on, to the Visayan Islands (Philippines). On March 28, they reached Limasawa Island, where they were met by eight men in a canoe.

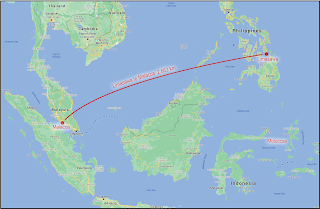

The men kept their distance, but to everyone’s delight, shouting, Magellan’s slave-interpreter Enrique of Malacca was able to converse with the men—proof they had reached Asia, proof that it was in fact possible to sail around the globe (no sea monsters, no falling off the Earth's end).

|

| Distance, Limasawa to Malacca. |

Magellan was vindicated, he had done what Columbus and others could not. The fabled Spice Islands were now within Ferdinand Magellan’s grasp. Enrique of Malacca, meanwhile, was nearly home.

By John Sailors

(C) 2022, by John Sailors.

Enrique's Voyage Profiles

Magellan's Real Circumnavigation, Enrique of Malacca Taken as Slave (Magellan, Part 1)

Schoolchildren around the world are taught the name Ferdinand Magellan[1]—“the first person to circumnavigate the globe”—many in grade school and again high school. But few people know Magellan's story, that he was killed in the Philippines halfway through that circumnavigation, and moreover, that he still came within 2,600 kilometers of fully circling the earth. Read more.

Spain's King Charles named Magellan captain-general of the Armada de Molucca, but from the start he had to enforce his authority with an iron hand. In Asia a decade earlier Magellan had been more soldier than sailor. Now as commander of a naval fleet, Magellan relied on his military fleet background to maintain control of his own armada. Read more.

Holy Roman Emperor Charles V Backs Magellan's Armada

Ferdinand Magellan’s Armada de Molucca was financed by Carlos I (1500–1558), the newly crowned king of a unified Castile and Aragon. Carlos was an eighteen-year-old Habsburg from Flanders who barely spoke Spanish. Between the time he agreed to back Magellan's expedition and its departure, he became Charles V, Holy Roman emperor, and archduke of Austria. Read More.

Juan de Cartagena Leads Mutiny Against Magellan

Juan de Cartagena, a native of Burgos, was the original captain of the San Antonio and one of the human obstacles Ferdinand Magellan had to overcome on the expedition. History labels Magellan and Columbus and other ship captains as “explorers” and “navigators.” Cartagena is identified as “an accountant and a ship captain” [1], not quite the swashbuckling image that inspires fifth graders in history class. Read more.

Frequently Asked Questions

• Who was Enrique of Malacca? (History/Biography)

• What was Enrique of Malacca’s Real Name

• What was Enrique of Malacca’s Cause of Death?

• Was Enrique First to Circumnavigate the Earth?

• Where was Enrique of Malacca from?

• Was Enrique of Malacca Filipino?

- EnriqueOfMalacca.com

- Enrique of Malacca on Twitter

- Enrique of Malacca on Facebook

- John Sailors / Enrique on Medium

- And, yes, Enrique might be 500 years old, but he was known as a kid, so of course he's now on Instagram too.