|

| Group of Tehuelches (drawn 1832). (Source.) |

Part 2 of series.

Part of the “explorer” mindset, a common reaction to encountering a novel people was the urge to kidnap a few to bring home as souvenirs. These foreign-looking men and women were presented alongside gold, spices, and other treasures brought back to Europe from the far reaches of the globe to present to sponsoring monarchs, evidence of great riches to be obtained in future expeditions.

Infamously, Christopher Columbus presented captured natives to Spain’s Ferdinand and Isabella, and Ferdinand Magellan, promoting his venture to their grandson Charles V in 1519, presented Enrique of Malacca, his Malay slave taken after the invasion of Malacca, and a young woman said to be from Sumatra as a sample of the people to be found in Southeast Asia.

|

| Mosaic, Columbus returning to Queen Isabella. (Source.) |

Magellan Captures Two Tehuelche

When Magellan's fleet encountered the Tehuelche,* a people they called Patagonian giants, Magellan decided to abduct a few to take back to Spain, but it was not an easy prospect. The wisely cautious and extraordinarily large Patagonians easily outran the Europeans, and they were far too large and strong to wrestle. As the expedition's chronicler, Antonio Pigafetta, wrote:

Our men had muskets and crossbows, but they could never hit any of the giants, [for] when the latter fought, they never stood still, but leaped hither and thither … Of a truth those giants run swifter than horses …

But Magellan came up with a cruel solution, a method to seize a few of the Tehuelche.

The captain-general kept two of them—the youngest and best proportioned—by means of a very cunning trick, in order to take them to Spagnia. Had he used any other means, they could easily have killed some of us.

The trick that he employed in keeping them was as follows. He gave them many knives, scissors, mirrors, bells, and glass beads; and those two having their hands filled with the said articles, the captain-general had two pairs of iron manacles brought, such as are fastened on the feet.

He made motions that he would give them to the giants, whereat they were very pleased since those manacles were of iron, but they did not know how to carry them. They were grieved at leaving them behind, but they had no place to put those gifts; for they had to hold the skin wrapped about them with their hands. … the captain made them a sign that he would put them on their feet, and that they could carry them away. They nodded assent with the head. Immediately, the captain had the manacles put on both of them at the same time. …

When they saw later that they were tricked, they raged like bulls, calling loudly for Setebos to aid them. …

|

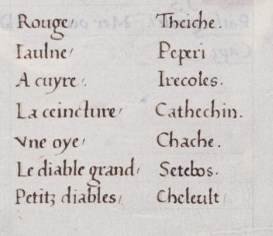

| Pigafetta's Vocabulary of the Patagonians, from a French manuscript, Yale University. (Source.) |

In a vocabulary sample Pigafetta later compiled of the Patagonian’s language, he defined Setebos as “their big Devil,” so it’s possible here something was lost in manuscript translation or Pigafetta’s interpretation: possibly the Patagonians were calling the Spanish “Setebos!”

One of them grieved so hysterically that Magellan sent a detachment ashore in search of the man’s wife, whom he was apparently crying for.

|

| The last two entries in Pigafetta's vocabulary: "Le diable grand, Setebos; petitz diables, Cheleulle." |

Unlikely Patagonian Explorers

Whatever level of communication Antonio Pigafetta established with the two captured Tehuelche, he could not have made them understand what was happening or where they were being taken. Even if Pigafetta had one of Star Trek’s universal translators, any explanation would have been ungraspable. “We’re taking you across an unexplored sea to get tasty plants that don’t grow where we live so we can take them back across the sea we just crossed and get rich …” There is no way the sixteenth century Tehuelche would have understood any of it.

Yet two of them—one who would be christened Paulo—were about to become briefly their region’s greatest explorers.

Both died at sea, one in the Atlantic, and Paulo in the Pacific.

It's a wonder what must have been going through their minds. These strange beings (the Europeans) had come from the sky in giant boats and now were whisking the giants away. To where and for what purpose?

_b_145.jpg) |

| Strait of Magellan, 1891. (Source.) |

The Patagonian that Antonio Pigafetta got to know aboard the Trinidad made that first journey through Magellan's strait. He would have witnessed the mysterious scenes of white, jagged peaks and rocky coves. Was this a magical river that led into the sky, to the end of earth and life as the giant had known it?

His European shipmates would have viewed the strait with equal wonder. They had left the world they'd known, as it was known, sailed well beyond the end of all maps even before meeting their giant. To them the passage may also have seemed like a river to the afterlife, and for many it was.

|

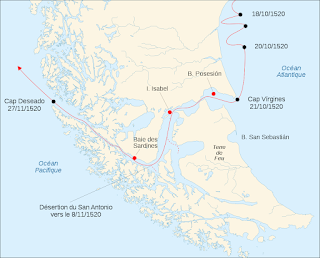

| Map, Strait of Magellan. (Source.) |

Soon they entered a new ocean, one so utterly calm that Magellan dubbed it the Pacific sea. Still waters and a strong wind at their sails sent them speeding into the unknown fast, but where they expected to find island paradises rich in spices and gold they found only endless open waters that each day cast an image of endless isolation in every direction.

The Patagonian would have witnessed many of Magellan's crew lose hope as starvation, scurvy, and impending death replaced thoughts of a world left behind. As he contemplated his own unlikely end, the giant would have seen these godlike crewmen face theirs.

Were these minor demons, Cheleule, that the giant found himself among, since they suffered and died just like people?

As Pigafetta wrote, "this malady was the worst, namely that the gums of most part of our men swelled above and below so that they could not eat. And in this way they died, inasmuch as twenty-nine of us died, and the other giant died, and an Indian of the said country of Verzin [Rio]."

Pigafetta noted that those refusing to eat rats were among the first to go. He also noted that the Patagonian giant Paulo ate rats without even skinning them first, so the giant likely survived longer than some of his captors.

Here is Pigafetta's account of the captured Tehuelche's end:

Once I made the sign of the cross, and, showing it to him, kissed it. He immediately cried out “Setebos” [great god] and made me a sign that if I made the sign of the cross again, Setebos would enter into my body and cause it to burst.

When that giant was sick, he asked for the cross, and embracing it and kissing it many times, desired to become a Christian before his death. We called him Paulo.

The name may have left one odd final thought for a Patagonian native in winter 1521 as he succumbed to death in the middle of Pacific Ocean: "And they called me Paulo."

By John Sailors, Enrique of Malacca's Voyage.

Patagonian Series

Part 1, Magellan and the Patagonian Giants

Part 2, Paulo, Magellan's Patagonian Giant

Enrique of Malacca Becomes First to Circumnavigate Globe

|

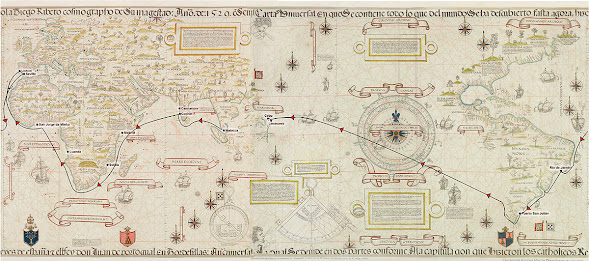

| Map of Enrique of Malacca's circumnavigation: Malacca, Lisbon, Seville, Rio de Janeiro, Puerto San Julián, Guam, Limasawa, Cebu.[1] |

On March 28, 1521, Enrique of Malacca became the first person to complete a linguistic circumnavigation of the globe—he traveled so far in one direction that he reached a point where his own language was spoken. Enrique’s journey began a decade earlier following the sack of Malacca, when he was taken as a slave by Ferdinand Magellan. A teenager, he accompanied Magellan back to Portugal, then to Spain, and finally on the Armada de Molucca to locate a westward route to the Spice Islands. More about Enrique of Malacca.